“Unless someone like you cares a whole awful lot, nothing is going to get better. It’s not.”

— Dr. Seuss

|

I was going to write about how we remember emotions, but saw a connection between this and project management, so I’ll defer writing about emotions until next week.

The connection is that they both guide us from different directions. Emotions are an ache, while executive decisions are an advertisement. It’s another good cop/bad cop, or carrot and stick metaphor.

Emotions are my primary interest. I think we’re entirely misunderstanding them by giving them a second class citizen status. We like to think we’re a rational people and that we make top down decisions, but it is on the basis of emotions and emotions only that we get divorced, start wars, and elect dysfunctional presidents. Given how firmly we’re controlled by emotions, it’s amazing we are able to resolve anything.

Fractals

I’m also a firm believer in fractals being everywhere in nature (Simply.science, 2018). You must get beyond the notion of fractals as pictures and understand them as migrating patterns. Whenever you have a structure on one scale that has evolved from and repeats a structure from another scale, you have a fractal evolution.

Boats are fractal. Small boats displace the water and float because they’re lighter than water. But if the boats are too small, of microscopic size, then different properties of water prevail and boats no longer work. Below the scale of one inch, the surface tension becomes too high relative to the viscosity and boats don’t sail right.

We can grow boats up to almost a mile in size, and they continue to behave in the same manner. Beyond that size, given our current technology, and their fragility and dynamics, they become impractical. It’s not the physics of water that’s a problem, it’s other practicalities. Nevertheless, within that range, from lengths of centimeters to kilometers, we can build and navigate boats using the same principles and designs.

Dreams

Dreams are fractal. We build them in an effort to find the self-similarity in our experiences. We’re looking for patterns in the scale, dynamics, and function of our experience. Our dreams reapply the structures we know to see if they work for other structures. We do this by conjoining them in theory and playing out “life experiments” with the results.

When yesterday’s new acquaintance reminds us of our successful childhood relationships, then, in our dreams, we’ll turn translate them into a dog to see if the relationship still holds, or maybe into a car, dragon, or sunset.

Our dreams don’t make sense as serial narratives because they’re not, they’re parallel narratives. Dreams are comparisons of different approaches to the same subject. If you recall your dream moments as a gradual morphing between different perspectives, they make a good but different kind of sense.

Seeing dreams as a lecture in executive planning makes them seem psychotic, but seeing them as a scrapbook of emotional reflections allows you to consider each scene as its own story, a story told by the relationships between the elements, not their progression in time.

Emotions

Emotions seem to come from nowhere because we don’t intentionally construct them. They’re not entirely reactive because we generally contain them. They’re like horses who know more about making progress than the people who ride them. We tell them where we want to go, but they remember the terrain better than we do and prefer to make their own path.

Our thinking selves lack emotional insight; we’re not open to our own emotional guidance. Our emotional guidance would very much like to find a stable grove and relax in it. There is something called “emotional intelligence,” but it’s misunderstood. We’re told emotional intelligence is your ability to get along, to empathize, and to understand others. This is just one consequence of what emotional intelligence really is, which is a bigger picture condensed to one of a few attitudes.

Each of our emotions has a vote in our role in any environment: happy, sad, frustrated, angry, bored, loving, etc. These emotions come to the fore without argument or justification, and they don’t care to justify themselves with evidence. The evidence for each of these emotions is built up from our feelings by our rational minds. A good justification seems compelling to our rational mind, but makes little difference to our emotional self.

The central question for the management of our lives is how to collaborate with our emotions. The horizontal approach is to build co-creative relationships. These are the best kind, but it seems we’re losing the knowledge of how to do it.

More commonly, we build vertical, authoritarian relationships. We refer to them as co-dependent because the power structure of each level depends on the other, but they could be better described as conjoined, separate, and unequal. You don’t get emotional equality from relationships built to fulfill unshared needs.

We’d have more successful marriages if couples viewed their endeavor in entirely practical terms, like a factory or an assembly line. The result would be a much lower rate of divorce and a much higher rate of stable, meaningless relationships. And this is what we did have before marriages were supposed to provide love between the partners.

Project Management

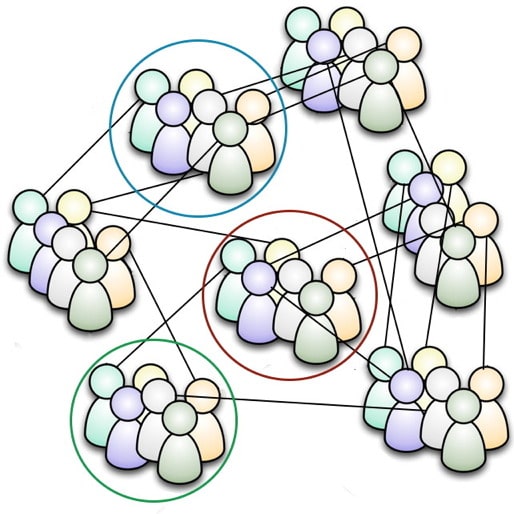

Projects are fractals. They weave patterns of self-similar relationships. We’re constantly trying to extend the structures from one solution to another problem. It often doesn’t work because we don’t see the underlying differences. A better understanding of fractals would help us recognize the patterns that appear within our projects.

Project management has traditionally followed the assembly line model. Specification are given at the start, agents engage to satisfy the requirements at each stage and then disengage, and at the end of the process there is a solution. The final solution might work if the design worked and all situations stayed the same. About 80% of the time, however, situations do change and the final result no longer satisfies current conditions are there is no way to repair it. Large, integrated projects fail most of the time.

This used to be okay. Corporations were big, innovation was small, and power was concentrated at the top. This still works in many industries, but in computer software it led to unsustainable waste and failure. That was the first industry where the dinosaur model failed to adapt to a rapidly changing business environment. Now, with more change partly due to computers and partly due to growth that has been triggered by computers, the failure of the top-down model is widespread.

Agile

Agile Software development (Beck et al. 2001) grew from environmental design in landscape and architecture. These new methods did not take root in that field, which remains bloated, hierarchical, and exclusive, but it did take root in software design. It will take root in the design of relationships between people and how we deal with our own problems.

Agile design is built on four values:

-

Meeting individual needs over following protocol.

-

Building things that function over creating sets of rules for how to make things work.

-

Collaboration over negotiation.

-

Responding to need over following a plan.

In each case, the intended scope is inclusive:

-

Needs: everyone’s needs.

-

Function: function for everyone.

-

Collaboration: at all levels.

-

Response: to all needs.

The idea is not to satisfy everyone always, but to be fully aware of and to make everyone else fully aware of what can be done, what resources are available, and what priorities are in place.

You may think following such a method in a corporate environment is a complete fantasy, and it is in many of the current corporate environments, but new corporate structures are being developed where this plan works. The results benefit everyone and, in particular, result in less waste and conflict.

Relationships

I don’t know if applying the Agile values to our personal relationships are more of a fantasy than applying them to a corporation, but many of the goals and obstacles to success are the same.

To some degree, corporations are simpler. Quality, efficiency, and satisfaction are easier to measure. On the other hand, getting a culture to change is harder than getting a couple to change.

There are some fundamental changes in perspective that underlie the Agile method that directly apply to relationships, and which would immediately improve them. For example, if groups—couples, families, or communities—adopted these precepts, things would be different.

-

Recognize and address needs before plans.

-

Find solutions that satisfy instead of defining rules that limit, delay, or constrain.

-

Work together and avoid compromise; design to join rather than separate.

-

Reorient toward change, rather than working to prevent change.

The nuclear family gave us stability. With it, we got depression, obesity, heart attacks, violence, divorce, disrespect, and rejection. I think today’s gender dysphoria is another result of the rejection of individual needs represented by the modern nuclear family. It is horrifying to watch television portrayals of families in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s and to think that people actually tried to live in this fashion.

Looking at today’s family structure, we see far more dysfunction than function. I feel I have become an expert in family dysfunction. I suspect you have some strong opinions yourself. We could create a good list of the problems common to today’s relationships.

Most of my client’s personal problems are connected with their current, past, or desired future relationships. Most of my clients are not implementing the Agile methodology. It’s fairly easy to get them to recognize the problems, but not to change their approach.

I’d like to suggest that changing how you move forward is more important than what you move forward. That a group’s attitude toward change is more effective in addressing change than their attitudes about what they’re changing.

I don’t mean to sound trite. I’m not saying that our problems will go away if we just put on a happy face. I’m saying that if we commit to the whole process rather than just our part of it, then the whole will improve. There are quite a few holistic things would help, that we are not doing, such as recognizing we are dependent on and responsible for the whole.

At some point, this leads back to honesty, collaboration, and open mindedness. I don’t think there is such a thing as peace without change, and so far, change has not been peaceful. This is true at every level and on almost every issue. We need a new methodology.

References

Beck, K., Beedle, M., van Bennekum, A., Cockburn, A., Cunningham, W., Fowler, M., Grenning, J., Highsmith, J., Hunt, A., Jeffries, R., Kern, J., Marick, B., Martin, R. C., Mellor, S., Schwaber, K., Sutherland, J., & Thomas, D. (2001). Manifesto for Agile Software Development, https://agilemanifesto.org/

Simply.science (2018). Fractals in Nature, Wiki Kids Ltd. https://simply.science/index.php/fractals-in-nature

Enter your email for a FREE 1x/month or a paid 4x/month subscription.

Click the Stream of the Subconscious button.